not the first time

It’s midday and I’m traveling north again, straight up through the belly of America. A week-old soda thickens to syrup as it rolls back and forth across the passenger seat and a grasshopper crawls slowly across my windshield, having hitched a ride at the gas station and found itself pressed into the glass by 60mph winds. I drive the speed limit, exactly the speed limit, for as long as I possibly can. Cars pass easily, skittering around the lumbering blue truck and its driver.

The fairy fern has died.

Cool weather and the smell of pine greet me as I make my way across an open stretch of road, only ever at exactly the speed limit. There is supposed to be bad weather ahead, a couple days ahead, that is, always a couple days ahead. In this perpetual autumn there have been no icy roads or sticky asphalt, only the occasional rain and long, clear nights and mornings clammy with dew.

I take to sleeping during the day, when my truck is kept warm by the sun, and driving at night when the traffic is minimal and I can run the heater. My conversations are confined to gas station clerks and motel owners and they all say the same thing no matter where I am or what time it is:

“You look tired.”

‘Autumn by the Wayside’ is, as far as I can tell, a book written in perpetuity. I should be narrowing in on the finish line now, I should be running out of places to see but there always seems to be something, something I missed in a region I know I checked off. The glove compartment is full of crumpled maps and charts that detail the trip so far, none of it cohesive or meaningful. There is no way to write a book like ‘Shitholes’ except for the way it’s already written.

Actually, that’s probably not true.

I am not an editor, that’s more to the heart of things. I’m not an editor in the widest sense of the word. I live my life like a bad novel, jumping from one scene to the next and making mistakes along the way and learning nothing, gleefully unaware that even a run-on sentence ends with a full-stop. There are a hundred ways to write any book but I only know just the one so I write what’s in front of me and then I move on.

Behind me is the scorched earth that once was ‘The Kat Cirkus,’ ahead of me is ‘A Prairie Dog Ghost Town.’

I’m somewhere in the middle.

-traveler

The alliteratively named ‘Wild West Waterworld’ boasts of having the longest waterslide in the county which, unless this specific Washington County is known for being particularly abundant in waterslides, seems like a non-boast to me. I’ll grant them they discovered a goldmine in their wedding of the old west and water themes with attractions named ‘The Revolver’ which is like a massive spiraling toilet bowl and the ‘Six-Shooter,’ where kids and adults alike are encouraged to race down six identical, steeply-sloped tubes and to skid madly across the shallow pool below. Less gracefully realized are the attendant costumes: tightly fitting swimwear and leather ornamentation in the vein of cowboy hats and heavy-looking holsters for plastic, water-spewing pistols. Some walk around in cowboy boots but they do so begrudgingly, even I can tell.

Reader, I have migrated south since last I wrote, perhaps unconsciously, or even semi-consciously, toward this entry specifically. The ordeal at Rest Stop #212 some time ago did a number on my psyche and the determinedly carefree nature of a waterpark has been something of a guiding light. The weather is warm, the breeze, gentle, and the staff willing enough to turn a blind-eye to a single man dribbling a flask of rum into a steeply-priced frozen slurry drink.

Life is not good, reader, but it’s certainly better than it was.

“It is said ‘A man is known by the company he keeps,’ and if we might extend that truth to a place then ‘Wild West Waterworld’s’ reputation is a poor one. There is very little wrong with park itself, the facilities are clean, the attractions well maintained, and the food mediocre, but the people who live there are of the worst caliber and it is this man’s hope that they stay put, so as not to be encountered on the outside.”

My leisurely consumption of the drunken slurry serves the double purpose of easing my nerves and masking my true purpose, to stake the place out disguised as a casual pool dude. With earbuds in and aviators on, plastered in a thick coat of sunscreen, I sit very still and watch people in a way that I hope comes off as passive and not creepy.

I’m right on the edge of a good doze when a guy trips over my ankle and apologizes quickly, catching up to a few of his friends ahead. Together they make up a group of thirty-somethings, no one peculiar on their own but strange for a sort of faded look they all share. The colors of their swim trunks are flat and washed-out, their skin pale to the point of translucency. The guy that tripped over me is blonde but his close-cut hair has taken on a greenish-yellow tinge. Together, they make their way up the tall staircase toward the entrance of ‘Boot Hill,’ a long, winding slide that twists carefully amidst the others, sometimes under and other times above, so that its exact path is difficult to parse from a distance.

I follow the group by blonde guy’s milky-red swimsuit, tracking their progress until they disappear, one after the other, into the depths of ‘Boot Hill.’ I scan the exits and I wait, relying on the guttural surety I’ve cultivated toward this very purpose, toward the purpose of spotting inconsistencies. Time passes and they do not emerge.

For once, I was expecting this very thing.

Someone involved with the production of Shitholes deemed it important to publish an appendix of bizarre maps in the back of the book, none of which adhere to any sort of scale or seem attached to particular articles. One of them is more like a collection of colorful squiggles than anything else but some of those squiggles are labeled and they are labeled with the names of ‘Wild West Waterworld’s’ slides. One such line is labeled ‘Boot Hill’ and several hastily written exclamation points alert the reader to its importance.

It takes only a moment to finish the slurry and only several, wheezing minutes for me to climb to the top of ‘Boot Hill.’ A woman is there to assure that I enter the slide feet-first, that I cross my arms and hold them to my chest. This, she says, is important. She tips her hat to me; I wink and immediately regret doing it. I can’t remember a time when winking was ever the appropriate reaction to anything. I escape into the tube.

‘Boot Hill’ starts off slow, easing me through a red, counter-clockwise spiral before dipping and picking up speed. Before long my body is sliding up the corners and noises from the outside become distant and echoed. The air inside is damp and close, I lose sense of how far I’ve gone and how much further I could possibly go. There is a sharp drop where the water seems to jettison me forward and down a length of green plastic faster than ever. I start to panic, knowing that whatever has warranted this waterpark’s entry into the book must be coming, that I slide toward my fate in sunglasses and swim trunks. I uncross my arms, try, in vain, to slow myself on the wall. There are no handholds, no place less slick than the last. In a final effort, I try to wedge my legs up into the ceiling but I only spin onto my back, now facing forward down the slide.

Then a splash.

I am underwater.

I try to swim up and find a solid concrete barrier. I try to swim up another way and break into the fresh air. A lifeguard’s whistle sounds.

“Dude,” he yells, “No head-first sliding.”

I’m at the bottom of ‘Boot Hill’ and those people are nowhere to be found.

I climb the stairs, dripping water as I go. The attendant at the top reminds me of sliding procedure. I refuse to look her in the eyes, afraid I’ll wink again, sure I would if given the chance.

My second experience of ‘Boot Hill’ is much the same as my first and by the third trip down I am feeling confident that the slide itself will not subject me to something on its own, that this is the sort of thing I need to figure out proactively. On my fifth slide, dampened and woozy, I depart once more from sliding procedure and uncross my arms, letting my fingers drag along the walls of the tube and, sure enough, just before the violent drop from yellow tube to green I feel the walls become rough and scratched. With a mad, twisting glance I spot a second exit just below the jettison point. By then, of course, it is too late.

I miss it again on the sixth, distracted and ashamed by the concerned look on the attendant’s face as I clamored in. The seventh time, finding she has been replaced with a stern-looking, fully-clothed man, I find the right system of pressure and leverage early and I slow myself down before the tactical precipice.

The texturing on the tunnel walls is undoubtedly the dragging of fingernails, a history of people scraping to a stop as I have. The water rushes around me as I maneuver, carefully, down and into the hidden slide. This is a black tube and the thick plastic allows no light to enter. I hold myself steady, gripping the ledge and wondering if this isn’t-

A rider thunders down ‘Boot Hill’ and out of the yellow tube, knocking my fingers loose and sending me into the darkness.

The rasping at Rest Stop #212 returns as soon as the pale green light behind me disappears and I plummet downward, the stagnant swirling in my ears the same as what existed in the restroom. My arms and legs reach out but find no purchase and I spin and choke on water, blindly led further into the depths of ‘Boot Hill.’

The panic recedes and I find myself shivering, pushed lazily along by a shallow current. It is still dark, reader, but now only a pathetic sort of dark. I stand and the warmish water is no higher than my ankles. I take a step and slip, like an idiot, back to my knees. The impact of my body echoes hollowly and I hear no noises from the outside. This is, by all accounts, still part of the slide.

“Hey,” someone says, “Why don’t you step out of the water? It’s slippery there.”

The plastic here is not as opaque as I had thought, as my eyes adjust I am able to make out a vague perimeter of the area, a rounded plastic room, bisected by the persistent stream of water at my feet. There are people in the room with me, mostly sitting, and piles of indistinguishable objects. As my bearings return I see a shadow reach out and offer a hand. I take it, and step forward.

The dry plastic is sun-warmed and easy to stand on, the air humid and stifling.

“Who are you all?” I ask, “What is this place?”

“We’re… wait, everyone I’m turning on a light for the new guy.”

The people around me grumble and then cover their eyes as an LED lantern comes on in the woman’s hands. She squints at me.

“We live here,” she says, answering neither of my questions.

The fact that these people live here is abundantly obvious now that I can see. Each person seems to have carved out their piece of plastic with a sleeping mat and a few personal items. There are a lot of old radios, limp looking books, and packets of food. Everything bears the telltale signs of slow chlorine bleaching and mildew rot. Even the people.

Especially the people.

“Why?” I ask, “Does the park know about this?”

“Of course not,” another guy chimes in, “That’s why we’re here. It’s paradise.”

A few of the faces around me seem to agree with him and the rest are mostly neutral on the matter. A couple look skeptical.

“Paradise is a strong word,” the woman admits, beckoning me over to what seems to be her mat, “Most of us were just looking to get away from the outside world for a while.”

“There are places like this all over,” the excitable guy chimes in again, “Places people forget about- old warehouses, walled-over bathrooms…”

“Vestigial sections of water slides?” I ask.

“We don’t know why this is here,” the woman says, “But we’re glad it is.”

“Hmm…” I say, and it seems to vibrate the room.

There is an expectant silence that drags on for several minutes while I make a show of observing the entirety of the place. It doesn’t take long.

“What do you do here?”

“Some of us knit,” the woman says, “Or read. Sometimes we talk to each other.”

“Only some times?”

“We don’t really have a lot in common except for the slide.”

This is the first thing everybody seems to agree on. ‘Boot Hill’s’ proper channel thumps noisily above us, sending another passenger along.

“Where do you go to the bathroom?” I ask.

“We use the park’s facilities for solid waste,” the woman says, a light red coloring her face.

“Look,” an older gentleman interjects, “the park chlorinates the water beyond what’s necessary to destroy common diseases carried by urine…”

“It’s not about disease, Jeremy,” someone else says, “It’s about ethics of relieving oneself into a children’s pool because you’re too lazy to use the regular restroom.”

The woman who greeted me remains red and quiet while the others join in the argument, highlighting this community’s third rail- whether or not they should be pissing into the stream.

If I try really, really, hard I can sort of see where these people are coming from. I suppose my truck and this stupid trip are equivalent, in some ways, to their longing for a place to escape to, a place that’s cut off from the world. It’s been a long time since I’ve met somebody I wanted to talk to more than once. It’s hard for me to tell whether that’s a result of my being constantly on the move, or if it happened the other way around.

The guy at the fairy fern place: I suppose I wouldn’t mind talking to him again.

If only for some clarifications.

No, I’m calling this one for me. I’m definitely better than these people, who seem to have motivation enough to bring little battery-powered DVD players down a water slide but not to use restroom facilities so nearby. I’m better than these people in a lot of ways and that realization is enough to put a big, smug smile on my face and a flicker of hope back in this road-weary heart. A little perspective goes a long way towards solving life’s problems, or, if nothing else, making them easier to ignore.

With little fanfare I walk to the room’s toilet/exit and finish my journey, emerging into the waterpark proper once more. I paddle to shore and walk back to my towel, packing the few things that seemed necessary.

“It’s pretty gross in there, huh?”

The woman from before stands behind me in a one-piece, her skin a pallid gray. She squints in the sunlight with eyes unused to the outside and we drip together on the sidewalk, two damp people in a vast, dry world. I scratch my leg and offer the only consolation that comes to mind.

“It’s gross everywhere.”

-traveler

It’s early in the evening, the time of day to start rolling up the windows- I seem to have driven my way into Fall, or lost a race with it and this morning I found the first hints of frost on my windshield. I’ll need to scrounge a blanket from somewhere soon, who knows what happened to the last?

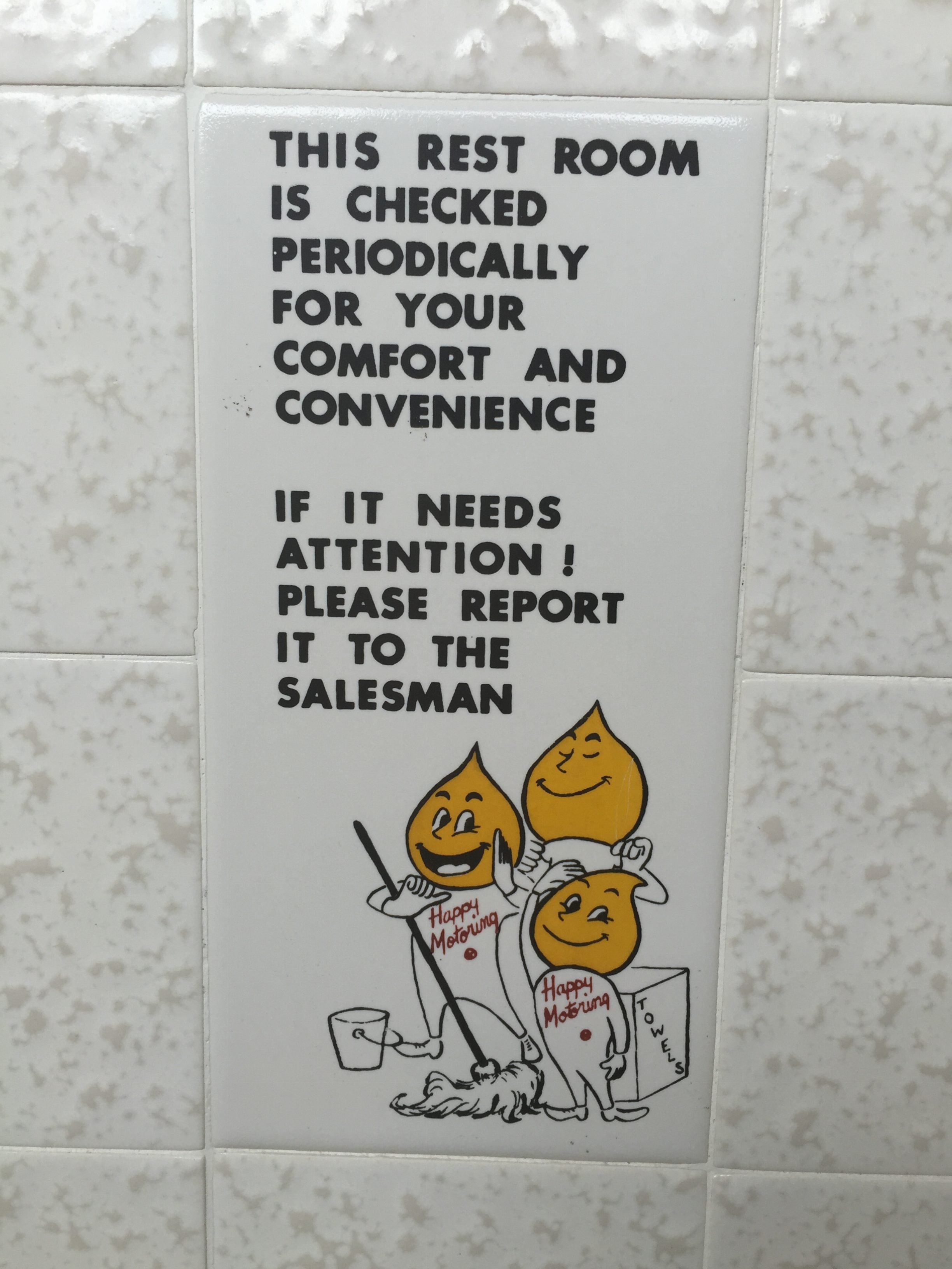

Rest Area #212 off the highway has me well and truly stumped. It’s given a write-up in Shitholes but is, by all accounts, just your normal sort of stop. There are bathrooms, reasonably clean, and a few old park benches outside, reasonably weathered. The information area is outdated and mildly vandalized, the pamphlets there warped and discolored by the sun. Who pulls off at a rest stop and takes directions from one of these, I wonder. Wouldn’t a person already have a destination in mind? Wouldn’t they have planned their trip such that they arrive at said destination according to a time table? I don’t think I would take water slide advice from one of these pamphlets, or water park advice of any kind.

Even if these slides are the tallest in the state.

Even if they are housed in a massive, heated structure so as to be a year-round affair.

Even if these kids appear to be in various stages of ecstasy, going down the slides.

Even if their parents seem to approve from the illustrated sidelines.

With a candy bar out of the vending machine I sit in my truck and wonder what it is I’m supposed to be looking for.

“For the safety of our readers, parking at Rest Area #212, off the highway, is not recommended. The mysteriously numbered Rest Area #37 just another hour down the road maintains similar facilities and has a pinchy, but well-meaning swing set for the kids.”

So I’m going to stop at #37 too, sure, but what’s going on with this place? It isn’t marked on the map in the book or the road map I picked up with gas. There wasn’t any signage to speak of until the ‘Exit for Rest Area’ announcement. Maybe I should have asked someone along the way.

The red car, the only other means of transportation in this lot, has been empty as long as I’ve been around. Nobody in the restroom when I was there, very few signs of life. That’s a strangeness of sorts for someone grasping at straws.

The car is empty, the reflection of my chewing the only movement. I kick the tires and find them full, don’t see any extraneous dust or foliage on the roof. A smell like cinnamon reaches me and I see the window is cracked, a smoker’s vent. The engine feels cold under the hood.

The bathrooms are still empty, I check the men’s and then, very cautiously, the women’s. These are cement buildings with few places to hide and they echo noises I don’t seem to catch. If you press your ear close, I wonder, would you hear the ocean? I doubt it. Maybe something else, though, some more stagnant body of water.

The women’s has a few more stalls than the men’s, that much seems reasonable, but the stall on the very end, which I had neglected to look at carefully on my first round, opens on a goddamn fucking staircase into the ground, I shit you not. There are plenty of reasons not to walk down the stairs, the foremost of which is that this still constitutes sneaking around the women’s room. It’s my job to look into these things, though, or it’s what I do instead of having a job.

I descend against my better judgment.

The old flashlight I left at Phil’s has been replaced with a newer model, a thing that emits cheerful white light even in places like these. The ghosts of my childhood were yellow like kidney failure under incandescent bulbs. Modern spirits are black and white, the way they were written in books. We’ve come full circle.

The young man at the bottom of the stairs is black and white and red all over like the joke but he’d dead and covered in old blood. There is no smell. Beyond him is a vast gray tunnel, far vaster and more gray than I’m normally comfortable with.

I step over the man and into the tunnel.

I was wrong before, when I said there was no smell. There is a smell like an old closet, like old, musty clothes. The air is still and difficult to breathe, it moves sluggishly into my lungs, seeming to resent the process as much as I do. My light finds a wall ahead, the way divides and moves almost imperceptibly downward with every step. The man behind me, the body, is facing the exit. He died trying to leave.

There is a toilet to the left of the fork, clean minus a few drops of brown urine under the seat. This stall caters to a niche audience, I would imagine. The tunnel continues to the right but before I am able to continue the body behind me, the man, begins to make noise. He starts to breathe.

The man’s breathing is audible all this way down the tunnel because it’s loud and labored. Under the dim light from the top of the stairs I see the rise and fall of his back, the expansion of his chest so dramatic that it seems, in the shadows, at odds with common anatomy. He swells like a balloon and then deflates, each exhale a violent, sputtering rattle. There is no movement, no sound, but for the man’s breathing.

I approach him cautiously but my footsteps change nothing. The man’s eyes are closed, his lips billowing. He has broken ribs, his chest shudders wildly underneath his clothes. The source of this man’s blood remains unclear.

The setting sun blinds me the moment I step outside. I run to my truck, pull the small first aid kit from my glove compartment. There is a hammer on the floor in front of the passenger seat and I grab that too, in case I need to protect myself. I dash back to the restroom, back down the stairs of the last stall at the end. The man’s breathing has lost its rhythm, each intake shorter than the last.

There are gloves in the kit and I put them on. I feel along his abdomen, afraid turning him over will only worsen things. The man’s chest has no structure, his ribs move freely under the skin. He doesn’t seem to notice me and his breathing continues to sputter out. Eventually it stops altogether.

I check his pulse, sitting very still so that I can be sure. His blood shines under the flashlight, lying next to me on the bottom stair. And then there is a noise ahead, like the tap of a foot. When I begin to adjust the light, smearing blood across its handle, I hear a polite cough.

Someone is sitting on the toilet, far ahead in the tunnel, their legs just skin and bone sticking out from around the corner, terminating in dusty blue jeans and old, leather shoes.

The man in front of me is dead, his heart motionless under my fingers.

The toilet flushes and the thing ahead begins to stand. A sickly, bulging stomach appears around the corner, clammy and pale under the LEDs.

The man in front of me is dead.

I run back up the stairs, fleeing in bloody gloves to my truck. The women’s room at Rest Area #212 lingers in my rearview mirror longer than seems normal, the place casting a shadow on my thoughts. I drive without the heat, afraid, in the short term, of its hoarse, rasping breath and thinking of the man who died in the tunnel and also of the thing that seems to live there.

-traveler

The least enjoyable sort of destination for me in all of this are the little businesses or attractions that are clearly run out of a person’s home. The Midwest is rife with these sorts of places and a certain type of person might find the idea charming or comfortable, a sort of shotgun-hostiness and a dash of American entrepreneurship. I wonder how a person’s mindset changes about the things or the places they own in order for these places to come about. When does a collection become something you’re willing to show off for money? When do you start wondering if you can make money off of local rocks? A man can only own so much rose quartz, after all.

My stomach sinks when I see the first sign advertising ‘The Museum of the Common Man’ as just fifteen miles away. It’s hand-painted and well worn, held to a tree by several long, rusted nails. Expectations were already low, to be honest. The name of the museum doesn’t go very far toward inspiring enthusiasm. Somebody who takes it upon themselves to erect a museum to the ‘common man’ is going to be political or philosophical in the worst ways and now they’re going to think I’m interested in hearing their spiel. I’m paying to be there after all.

‘The Museum of the Common Man is the brainchild of a guy that thinks he’s one of the less common. It’s a shrine to the intellectual ego, built before the proliferation of the online communities where modern egoists go to commiserate or knock each other down. This man, left alone, has built a shrine to himself and accidentally fulfilled his promise. Do not visit expecting to enjoy yourself.’

A low bar, as I said.

The museum grounds are just off the highway, the sort of place that retains a year-round dusted look from the constant passing of semis and the glare of a sun without obstacles. A house sits in the front, too small (god, I hope too small) to be the museum. The likelier place is the extended barn-type building out back where somebody has maintained an optimistically sized parking lot.

A human-shaped cloud of dust pulls away from the porch as I pull into the lot. The man has the look of someone prematurely aged- his hair has maintained a golden brown but his face has the deep, downward sloping lines of a chronic frowner. He walks up and leans on the fence at the edge of the lot, gesturing me into parking like the place is crammed full.

“Here for the museum?” he asks once I’ve stepped down from the truck.

He’s a spindly guy, rail thin under the flannel shirt and jeans and I’ve got more than six inches on him. There’s a knife in my back pocket, a flip-open thing with the modern sort of safeties that I’d probably fumble with during a fight. Probably most important, I’ve got my running shoes on in case I need to get out quick. These are the sort of precautions that keeps a guy alive when he follows strangers into barns.

“Yep.”

“Right this way, then.”

The path out to the barn is lined mostly with low, dry-looking brush but occasionally we pass by an old piece of farm technology, long rusted, and each piece has a little sign that describes what the thing used to be (tractor, backhoe, etc.) and what they are now: ‘Failures of the Common Man.’ Looking at all those signs I start to think maybe this is all a big joke which, in my mind, might make this experience a little more worthwhile. Could be this man’s the cynic’s cynic.

“What’s admission like here?” I ask and he spits.

“Fi… er, ten dollars. Year pass is a huhnerd.”

Is that another joke? I try to chuckle but by the time anything comes out the moment’s passed. I mask it with a cough.

“Dusty out here,” he says as we reach the barn door, “I’ll have ter go turn the place on ‘round back, won’t take but a minute.”

He stands silent until I realize he’s waiting for payment. I hand the man his ten bucks and he disappears around the side of the building.

My stomach rumbles and I check my watch. It’s just past noon, about the time I’m usually scouting around for a place to grab lunch. I flip through Shitholes to see if there’s any recommendations nearby but it’s got nothing in the way of food for a couple hundred miles. There’s a bag of jerky in the truck that I bought out of a guy’s shed. His was a shriveled Noah’s Ark, two of each animal, vacuum packed and sealed. Mine was a purchase of whimsy, a veritable sampling of all God’s creatures. I wonder if I’m allowed food inside the museum, but then, the truck is so far away now.

A generator coughs itself to life behind the barn and the gray smell of exhaust reaches me before the man does. He’s changed clothes, or, he’s thrown on a jacket that has the name of the museum embroidered over his heart. On the other side it says his name: William.

“William’s a common name for a guy,” I say, trying to conjure the half-joke from before.

“Go by Will, mostly,” he says, “Say it takes will to rise above the common pitfalls and passions o’ the folk ‘round here. Step inside when I call ya.”

Will slips in through the barn doors, careful that I don’t peek in and spoil the surprise. A smarter man than me might seize the opportunity to escape, leave Will with his ten dollars and the smug assurance that I, as a common man, simply grew too afraid of facing myself in his philosopher’s mirror. Who could have guessed that the burden of humanity would fall on the shoulders of Will, a Midwestern-

“I said come in, boy,” he yells.

So I do.

The barn door isn’t used to being opened more than a foot or so, just enough to admit a slim frame such as my own. The inside of the barn is dark, the lower level empty except for a stool in the center. When I stop to try to make sense of the modified ceiling above me I hear Will’s voice from the dark rafters.

“If you’d take a seat, sir, we will begin shortly.”

The stool is on a little platform, built into the ground and an arrow, painted on the platform says:

“Face here to begin.”

I sit on the stool and the legs give out completely, the shattered wood splintering as though under some great weight. On my ass I see the thing’s nearly turned into sawdust, that it likely was never anything more than cleverly stained balsa wood tubes. Tubes filled with sawdust. The barn door creaks closed.

“The common man is a trusting critter,” Will’s voice comes over a speaker system, “The first folly of the common man is a tendency ter follow directions.”

“Fuck you,” I mutter at the darkness above me but as I try to leave I find the barn doors locked.

“The common man don’t much like seeing hisself laid bare…”

It’s not so dark in the barn that I’m not able to see that the walls are lined with other exhibitions. A spotlight comes on above me and illuminates a dusty mannequin across the room and Will’s voice drones on, assuming I’ll catch at least some of it.

“It weren’t until man began to settle that a clear division began ter take place between the common an’ uncommon folk…”

An absurd scene lights up across the room, two cavemen representing some intellectual split that happened in time unknowable. I realize the first mannequin has a mirror for a face, no doubt Will’s take on poignancy. The added light helps me to spot the latch holding the barn door shut and I let myself out. Will keeps talking inside, his voice muffled by the thick wooden walls. The sun is downright blinding.

What an asshole.

I’m only a few minutes down the road before I start to get this ill-meaning itch, the feeling that I’ve somehow left without fully completing whatever experience Shitholes suggests (or at least documents). There’s a part of me that will always wonder what I missed. I make an awkward 3-point turn on the road and piss off a dude in a janky looking sedan and then I’m headed back to Will’s farm, determined to see what his deal is without having to further interact with him. I leave the truck about a quarter-mile out and walk a ways until I find a comfortable shrub to sit behind while keeping The Museum of the Common Man level in my thrift-store binoculars.

Will comes around the barn a few minutes later, still wearing his embroidered jacket. He eyes the barn door for a moment and fiddles with the latch. Then he looks up, up at the sky, and he stays that way for a long time, shoulders slack, breathing even, mouth slightly open. He stays like that for long enough that I start examining the sky myself but there’s nothing. I try to focus on Will, try to see if his eyes are open or closed or if he’s blinking at all. Finally, he just brings his head back down and walks to his house.

As I wait for the sun to set on The Museum of the Common Man I take a closer look at the surroundings. The path leading to the museum proper is carefully lined with old relics but the field out back has its share of scrap wood and rusted tin. A truck stops to exchange mail with Will’s box and putters away. A country mailman must have a lot of time to think during the day. Will emerges from his house as the truck disappears and shuffles a couple letters on his way back inside.

I sneak closer in the dark and wait for Will’s silhouette to give his location in the house away. When it does, when I see he’s in the kitchen, I move in past the socially acceptable limit of trespassing and start trying to catch glimpses of his home life. The light of the kitchen falls into his bedroom which has a clean floor but cluttered shelves. The living room looks dusty and there’s the impression of a man in the sofa. He’s still got a box TV.

Back in the kitchen Will is chopping tomatoes and throwing them into a pot on the stove. The knife is too dull and he crushes the tomato every time he tries to make a cut and then he ends up just tearing the mashed piece away and calling it good. Tomato juice leaks onto the floor before he pulls a rag from the fridge to mop it up. After a while, once the chopping is done, he stares into the pot like he did into the sky, occasionally stirring but mostly doing nothing at all. He coughs and doesn’t cover his mouth.

I’m strangely riveted by the whole thing and Will makes no attempt to conceal his home life. No shades are drawn, no cautious looks spared for the windows. He pours the pot into a bowl and take it into the living room to watch the evening news. He falls asleep on the couch, wakes up an hour later and stumbles into the bedroom. Under the covers he falls asleep again, his breathing even. It’s past midnight now and my own breath emerges in a fog.

What a miserable life Will must lead what with his being alone and being a shitty cook. The Museum of the Common Man truly was a shithole, but I feel at least a little better knowing the guy who runs it isn’t all that much better than…

Wait…

-traveler

© 2024 · Dylan Bach // Sun Logo - Jessica Hayworth