There are fewer and fewer sacred places on this earth- fewer places unworn by the feet of travelers. Some of the roughest edges of the Wayside have been smoothed by the great stampede of people like myself, who look for an escape here and, finding that here is much the same as everywhere, attempt to squeeze in through or into the dirty seams and cracks of places that seem unbroken. Those places do exist, but they’re growing thinner and dirtier and the internet has made travelers lazy.

I’ve grown lazy.

‘The Universal Receiving Tree’ in California is a marvel for the mainstream. It is a massive redwood that, over many, many years, has been grafted with the branches of nearly a hundred fruiting and flowering trees. It sustains these branches, requiring little maintenance beyond the initial grafting supports. It blooms in the spring, summer, and fall and creaks like an old skeleton in the winter, a hodgepodge monster among its neighbors, none of which have boasted the same flexibility.

I’m starting to sound like the book, I know, but the book says something else entirely.

‘Oh, a pretty apple. Oh, a juicy orange. And both? Amazing!

That’s what you sound like when you visit ‘The URT.’ You sound like someone who has never been to a grocery store. The sad truth of the matter is that ‘The URT’ isn’t doing anything particularly interesting on the surface. Tree grafting is an old, if not tedious, technique and ‘The URT’ is just a prize pug at the dog show: dolled up and wheezing for the masses. Did you know ‘The URT’ draws a diverse population of butterflies the likes of which can be found nowhere else on earth? Did you know that the tree’s seeds are collected and burned to keep its secret proprietary?

Did you notice there aren’t any squirrels in that tree? No insects around its base?

The Wayside is the metaphorical shoulder of the highway- the place that exists between road and ‘other.’ But metaphors are limiting. Sometimes the Wayside is as much the places above and below the highway. Take, for instance, ‘The URT.’ Why does nobody collect the fruit that falls until after closing? And why does the parking lot never clear?’

It’s difficult for me to see ‘The URT’s’ park and its structures as anything but shady, having first read the guide’s entry. The rest of the forest is entirely open to the public, with the usual restrictions regarding hunting and camping. ‘The URT’ stands alone, fenced off at a distance one expects from a tiger’s enclosure. The site is overstaffed and manned by people who take their job way too seriously if you believe their job is to simply guard a tree. And life does avoid ‘The URT’ at ground level. It’s difficult to tell for sure from the raised platform, but nothing obvious moves down there. No bugs. No rodents. Birds stick to the branches. Bees stick to the air.

When I look too long a man pulls me back and tells me I was leaning too far out.

He’s the man I ask about closing procedure.

“The thing is,” I tell him, “I’ve got a friend that’s got a friend that did the underground tour, you know. Off the menu. And he said for money, for like, $500, it can be arranged.”

I don’t have friends, as you must well know, and I don’t always have money. The man asks for more but I stand firm. I’m not good at haggling- I just don’t have any more money than that to give. He accepts when I offer the money upfront, and he tells me to meet him in the parking lot an hour after closing.

The camper is not inconspicuous in the near-empty lot and I make it more conspicuous by peering through the shades every few minutes, thinking that a rogue leaf is someone coming to tell me where I should and shouldn’t be. When someone does come to the door, I don’t hear approach at all.

One tentative knock. Two louder knocks after that. The knock of someone second guessing what they’re doing, someone nervous, I think, which puts us on even ground.

I open the door and find a woman. She’s younger than me, dressed in unbuttoned flannel and unlaced boots. I recognize another traveler and she must have recognized the same in me.

“Are you waiting for the tour?” she asks.

“Yeah.”

“You want company?”

“I have company,” I tell her, and I gesture to Hector, wheezing on his bed in the corner.

“What’s wrong with him?”

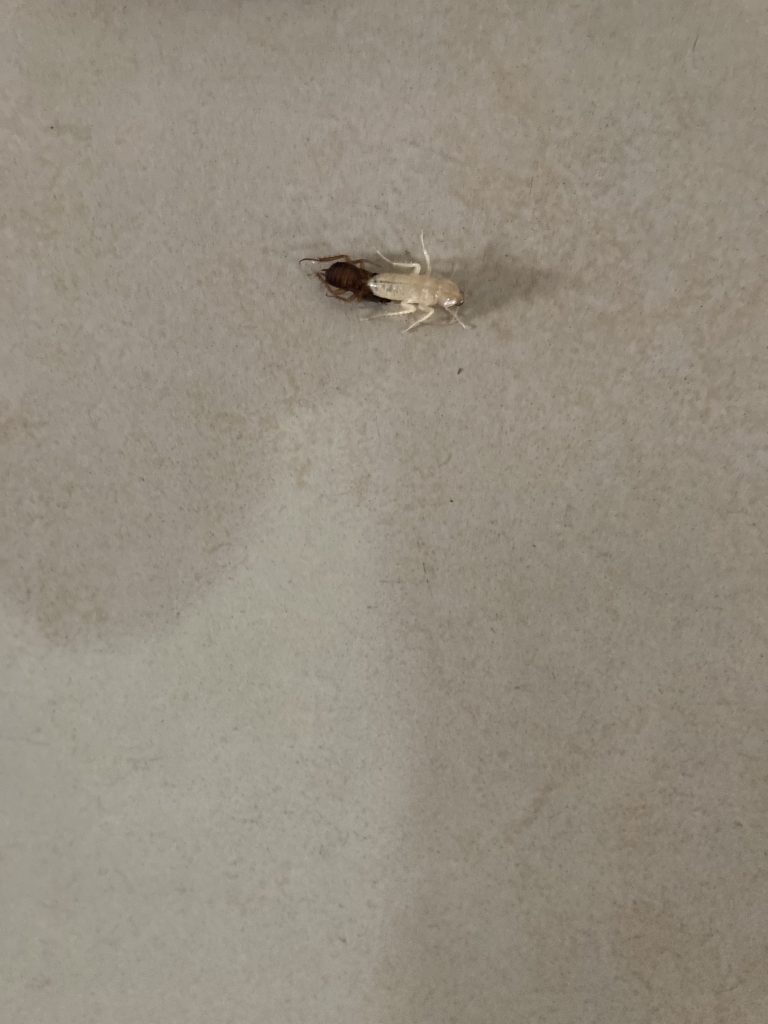

The wheezing started a couple weeks ago. Then he got sluggish. The couple vets I’ve seen tell me it could be anything. The rabbit’s old and he’s got more miles on him than most. They all agree that it doesn’t look good. Lately he’s taken to chewing a hole in his back, a habit that’s landed him in a cone.

“I don’t know.”

“I’ve got a coffee pot in my car if you’ve got electricity in this thing.”

“Sure,” I tell her, “I could use coffee.”

The man is late coming to retrieve us, but he makes good on his promise. He doesn’t blink when I haul along a sick rabbit. Eve, the woman, side-eyes me.

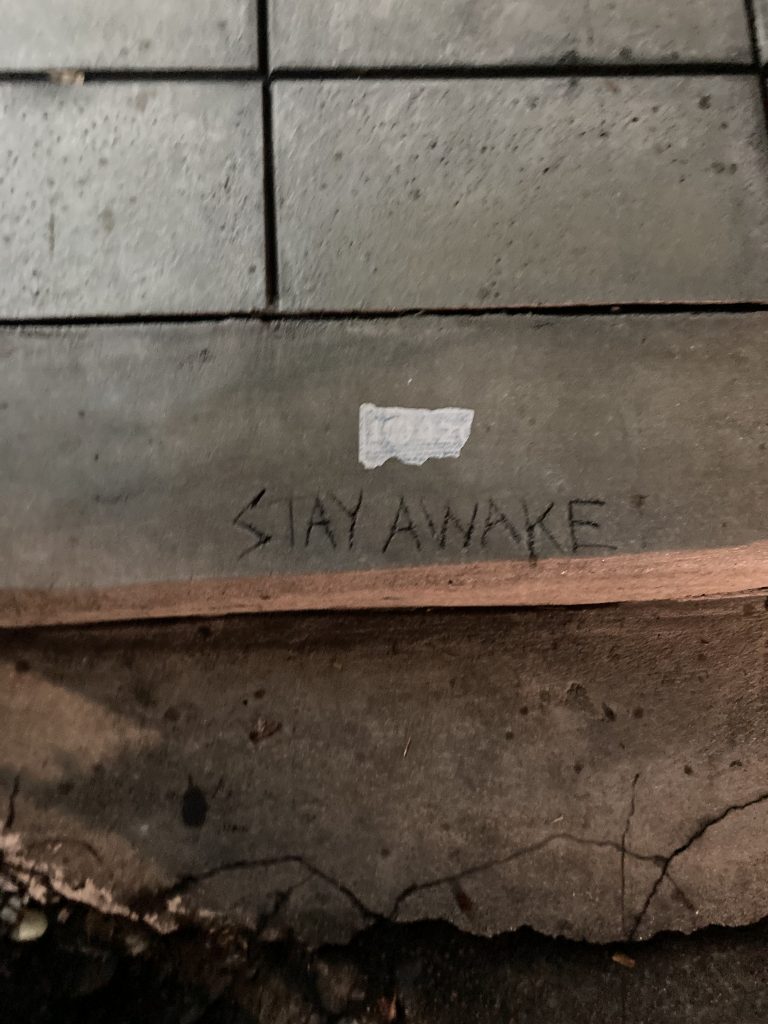

Through a back room and down a series of cement stairs, we find ourselves in the hollow chamber that allows for access to ‘The URT’s’ roots. They emerge from the ceiling and reenter the soil through the floor and walls. A number of people in lab coats mill about the exposed roots, examining the illicit grafts. It’s mostly animals and pieces of people. There’s something that looks like a robot across the way, but when I stare too long one of the uniforms gestures at our guide and he pulls me away.

The tour is wordless until we reach an alcove in the far wall. The earth is exposed, there, and the grafts go mostly unobserved the employees. Our guide points with his chin:

“Deposits.”

I take off Hector’s cone and stroke his head. Then I set him close enough to the roots that the ragged flesh around his chew-wound touches the wood. He doesn’t move from the spot.

“This keeps things alive, right?” I ask.

“It sustains them,” the man says. It’s a practiced deflection, but sustaining is enough for now.

I look over at the woman and she shrugs: “More coffee?”

We camp there, in the lot, until someone finally arrives to tell us we have to go.

-traveler