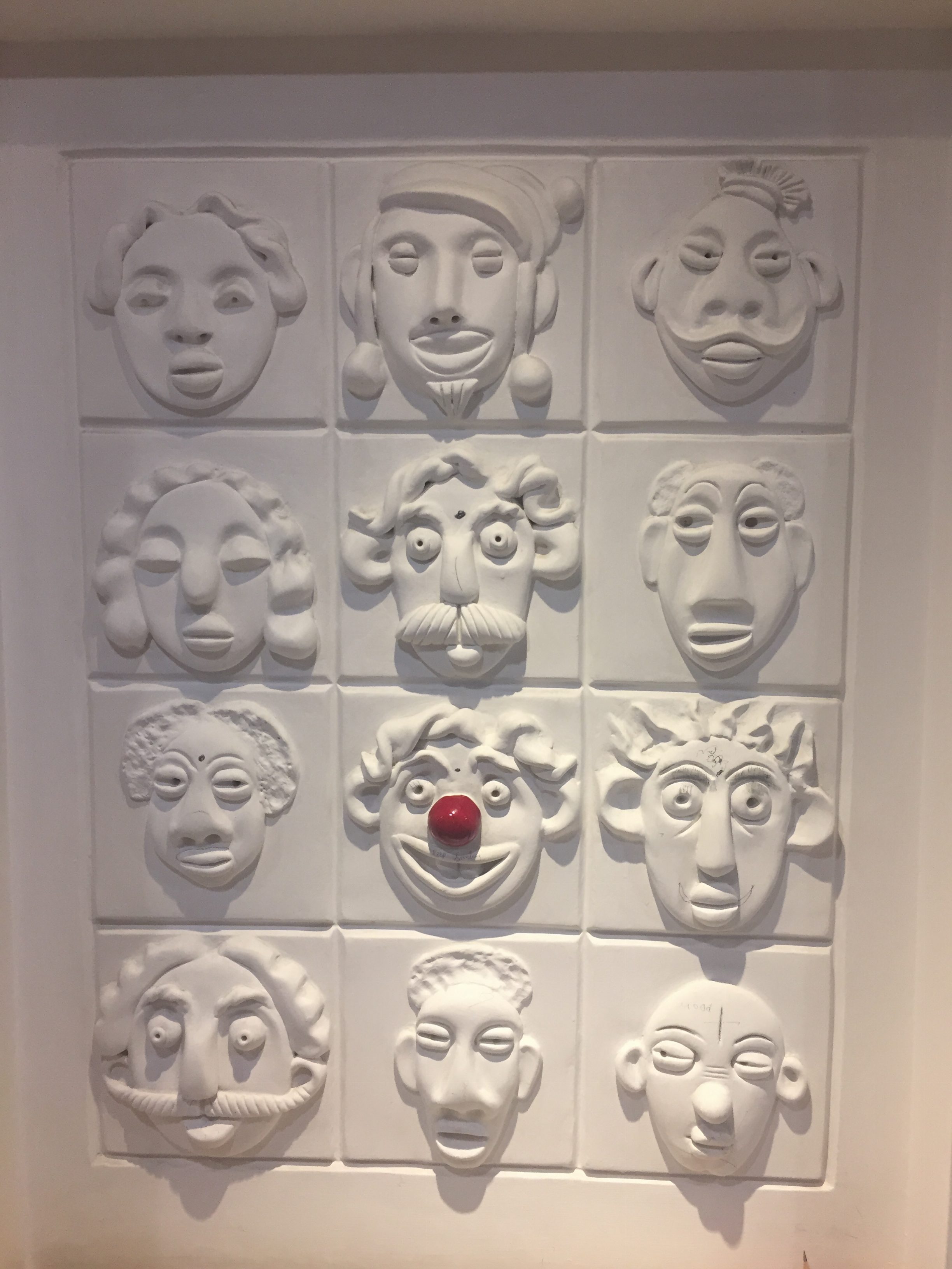

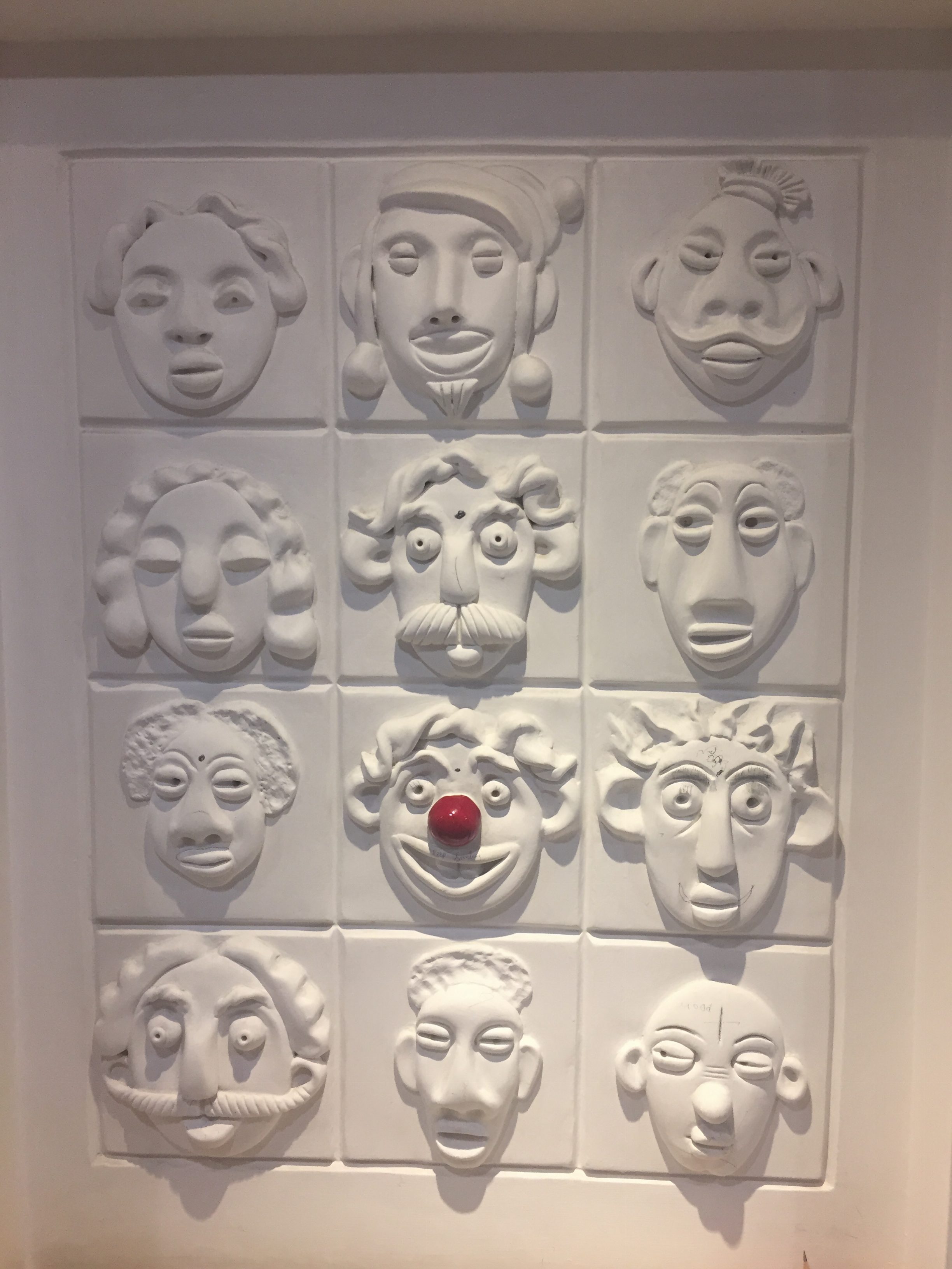

splash of red

The traveler explores the American Wayside, verifying the contents of a mysterious guide written by a man with whom he shares a likeness and name. Excerpts from ‘Autumn by the Wayside: A Guide to America’s Shitholes’ are italicized. Traveler commentary is written in plain text.

What a relief it was, as a child, to be through with our parents’ insistence on medicine, to mistake relative wellness for health. It is a truth of adulthood, that sickness is a river and health is the rope-bridge that we navigate above it, a bridge that weakens invariably over the years, a bridge that we inexpertly patch each time a plank gives way and we fall through. We wish for medicine, then, we would take it eagerly, no matter how sickly sweet, no matter how it catches in our throats. until there is no medicine left on earth that can strengthen us. We wish for medicine when we realize that the river will certainly outlive the bridge, when we realize that, even if the river dries, well, it’s still a long way down.

I cling to my medicine, a long-familiar dosing that keeps me going even in the good times. I dip a little more, for the pain, and find it difficult to return to the old measure. A dip becomes a pit and I am lost for a while, there, in the darkness.

‘It’s an effective gimmick, that you find the door of the ‘Voice Depository’ locked, that the only indication of how to proceed is a plastic ring, dangling from a short piece of string where a bell would normally be. A hesitant pull opens the door and elicits the entry message, delivered in a voice one might attribute to a world-weary six-year old.

‘I’m sleeeeepeee…’

The ‘Voice Depository’ is a collection of sound-boxes, torn from dolls and plush animals and arranged as an interactive exhibit. The self-guided tour reads like a gentle conversation with an elderly neighbor- a series of confused memories with occasional points of intense clarity. Niche sects of modern day pagans claim the voices can be read like a scattering of bones or cold dregs of tea. They have published their own ‘suggested’ walkthroughs, tailored to questions you might have for the mournful boxes and their seemingly disparate messages.’

There is nobody to greet me at the information desk just inside the door. A sign, there, informs me that the ‘Voice Depository’ is run by volunteers and that, this week, I am being hosted by ‘Gray Fellowship, #103.’ I stand, for a moment, to see if anybody will object to my entering and, when nobody does, I take a pamphlet and push through an aged turnstile.

The ‘Voice Depository’ categorizes its collection by ‘activation method’ and, within each section, attempts to arrange the pieces chronologically by suspected manufacture date. The collection in the ‘strings’ room hangs from a high ceiling, each box hovering a yard or so above its corresponding sign. I pull one at random:

“My name is Billllll.”

The height difference isn’t much but it’s enough that the voice, already slowed with age, seems to retract ominously as it speaks, floating, as it were, toward the ceiling. I retrieve a crumpled piece of yellow paper from my pocket, notes I made regarding the bitter online disputes of the pagans, and see if Bill’s voice features in any of their claims. It does not.

Much is said about a particular area of this room, where five boxes hang confusedly over four signs and one hangs an inch or so above the rest. The outlier is clearly old, its string cut and knotted together in several places and its song-voice worn down like a rock in a stream. I pull it and hear a deep, slow verse:

‘III fellll for youuu…

Like rain upon the roooad.

I wait in puddles…

Until you can be told.’

I pull it again:

‘III fell throoough…

The lane where it erooodes

I stay in trouble…

Under the dusty roooad.’

This is the heart of everything written about the ‘Voice Depository,’ the varied interpretations of what the particularly old boxes say and whether they say the same thing each time. Neither of my recordings are particularly unique, in fact, this box is referred to as the ‘Lost Lover’ by those committed enough to name them. I pull a few more (Good morning, mommy!) for the sake of saying I had (We’re BEST friends!) but find nothing particularly inspiring among them (Looks like trouble over the ridge…).

I look up, far up, into the confused mess of string at the center of the ceiling. There is supposed to be a hidden box there, a box called…

“That’s a myth!” someone says behind me, an older man in a jean shirt and a leather vest. “The ‘Devil’s Voicebox,’ right? Never been there.”

“You’re the volunteer on duty?”

“Yep. Carl’s my name, member of the One-Oh-Three Grays.”

“Bike club?” I guess.

“Sort of,” he says, “Gray Road Theorists believe that certain roads in the U.S.-”

I should have known better- it’s a safe bet to assume any gray-themed fraternity is one of their bunch. Luckily, Carl’s not an evangelist.

“Your voicebox, though, that’s a myth. I suppose you’ve already tried out this little guy-”

‘I’ll tell youuuu…

The pain I have bestowed.’

“I got that one,” I tell him, “Just looking around.”

“Well I’m off my smoke break now in case you need anything.”

Carl trudges off as the Lost Lover ends his third rendition, rising just a little over its brethren.

The button room, which displays the innards of squeezy-type toys, hold little of interest. A lot of laughing, a couple burps, all noises you might expect of things made to be coddled. One stands out from my notes, a box that is supposed to scream, but sounds, to me, like staticky laughter run through fading wires. We hear what we want to hear, I suppose.

I brace myself before entering the room of movement activation. Inside are the boxes of toys that look out for you, that activate when you walk by. This is the room of tea leaves, as it were, because walking directly to the center, rather that following the roped path, puts you in range of all of the exhibits at once and, well, I think witchylady33 will say it better than me:

‘There, in the cacophony of child-speak, your future unfurls.’

I don’t believe in much. Things I expect to happen often don’t and, just as often, it seems, things I hope wouldn’t happen, do. I don’t know that my experience in the wayside has prepared me or made me a better person or worn me down or made me humble. I look back on my own writing, a year’s worth, now, and wonder if I have changed at all or if I carry on much as I did- the same person in different places.

I hold my breath and step into the room, directly into the center, and I wait and hear nothing at all and I continue to hold my breath and wait until it becomes clear that nothing is the only thing that is going to happen. I am in the middle of a round room and a hundred little boxes eye me with their sensors and say nothing.

And, in the silence, something occurs to me.

-traveler

‘The niche success earned by a handful of ‘dining in the dark’ eateries has had the unfortunate effect of inspiring several businesses with less suitable models to turn off the lights and hope for the best. For most, this spelled the embarrassing end of an already-failing enterprise but ‘Ma’s Midnight Petting Zoo,’ with a name better suited for a swinger’s club, has proved the plucky underdog of the bunch.

‘Ma’s’ survives, in part, by cultivating an air of mystery, mixing a little ‘peeled grapes are eyeballs’ in with their ‘interacting with nature is important’ mission statement. This also serves to downplay the real mysteries. Who is Ma and how does she maintain an omni-presence on all tours? How are so many animals represented in a building that, judging from the outside, couldn’t allow for more than a thousand square feet? And what exactly is the nature of these animals, given that nobody has ever seen one enter or exit the zoo?’

‘Ma’s Midnight Petting Zoo’ opens with an airlock-type room, a room that you enter and are stuck in until the door behind you shuts and casts you into darkness before the door in front of you, leading to the lobby, unlocks with a subtle click.

‘This is fun,’ I tell myself, fumbling forward to the second door, ‘This is part of the experience.’

With the second door closed behind me I stand, in further darkness, and breathe quietly until I notice the breathing of someone else in the room.

“Hello?” I ask, and young woman’s voice responds.

“Oh!” she says, “Sorry, I didn’t see you come in!”

There’s a second’s pause before she speaks again.

“We’re trying that joke out. How was it?”

“Apt,” I tell her, toeing my way forward, “But it might be better to let people know where you are.”

“That’s what I said,” she continues, “Let me sing you to the counter.”

The woman sings a nursery rhyme I don’t know and I follow the voice with my arms outstretched, grasping at her like some malicious, creeping spirit. I stumble several times on obstacles that are not there but always manage to catch myself in the spinning darkness. Eventually I bump into something solid and the woman ends her song.

“Did you bring a friend?” she asks.

I reach back behind me, suddenly, sure that the stranger is there.

Nothing.

“It’s just me,” I tell her, “Why?”

“Pleasantries,” she says, “That’s fifteen dollars, then.”

I have my credit card halfway out of my wallet when the woman stops me.

“Cash only. We have a sign here but, well…”

I put the card back and try, in vain, to suss out differences between the bills by touch alone.

“You can just hand some to me,” the young woman offers after a polite silence, “My name is Elle, by the way.”

“You’re wearing night-vision goggles or something?” I ask, blindly holding the money ahead of me.

“No,” she says, “See?”

Elle’s hand appears on mine and she brushes her face across the underside of my wrist. The unwelcome intimacy is relieved, in part, by a quick return to business as she plucks the bills from my hand and types loudly on a cash register.

“Your eyes adjust,” she says, leading my fingers to the change, “It takes a while, but your eyes adjust.”

Elle sings me to the entrance of the zoo, a less intuitive process that involves my keeping her voice exactly behind my back as I move toward another door. When I find it, Elle’s singing drops off and she yawns.

“There’s a guide rail just inside and to the left,” she says, “Keep your hand on that and move forward. Ma will catch up to you in there and give you a little information about the animals.”

“Are there normally more people here?” I ask, but she does not respond.

“Elle? Hello?”

No answer.

I take a breath and exhale.

The heavy smell of a barnyard greets me on the other side of the door. I find the guide rail and wait, uncomfortably listening to the small noises of a hundred living things. When I tap my finger, something huffs in the dark nearby and I feel the inquisitive sniffs of some creature on my hand. I recoil, and am lost.

“That’s Henry,” a voice says, “He’s our resident goat. Must like what you had for lunch.”

“I haven’t eaten lunch,” I say.

“Must like you, then. Why don’t you find the rail and we’ll continue.”

It takes me a moment, the guide rail seeming further away than I moved. Back in position, the invisible goat takes to sniffing my hand again and Ma lets me stand there, experiencing it.

“Why don’t you give old Henry a pat?” she says after a while, and I oblige. The goat takes to dodging my hand, relatively uninterested in it as an active entity. “That’s good,” Ma says, “Walk a little further.”

It’s impossible to tell where exactly in the room Ma is speaking from. It doesn’t sound like a PA system; her voice comes softly, always a step ahead or a step behind -far enough that I raise my voice when I speak to her, close enough that I worry I’ll step on her feet.

“This is our bunny box,” Ma says, stopping me again, “The softest thing you’ll ever feel.”

I reach forward and feel around to no avail. I’m about to speak up when a familiar snuffling appears on my hand.

“Henry?” Ma asks, “What are you doing there you silly goat? Are you looking for another pat on the head?”

Ma is quiet for a long time before I realize she’s waiting on me. I pat Henry’s head and continue.

“We like to have a little laugh early on,” Ma says, “A couple’a friendly jokes before we get to these scaley fellas. It’s mostly families through here, not big guys like yourself who probably don’t worry so much about putting their hand in a box of snakes in the dark. Just little garters, that’s all.”

I reach forward and immediately feel the head of a curious goat.

“Well! Our friend Henry likes your pats like he likes his carrots- plentiful! Speaking of which, we’ve got some carrots waiting there if you want to give him a little treat. Just a little to your right and about waist height on a tall guy like yourself.”

I grope around, frustrated, until I find the box and reach inside. Something there moves across my fingers and I jump back.

“There’s those snakes!” Ma says, “Guess poor Henry will have to go without for today.”

“I think I’m ready to go,” I say, addressing the room at large, “I’ve… got to be somewhere.”

“You don’t want to meet the others?”

“How many goats do you have in here to meet?”

“Well!” Ma scolds, “If you’re going to be a sourpuss go ahead and follow the guide rail a little further, turn left when it splits and then right again following that. It’s the shortcut we use when the little ones need the restroom.”

I navigate the dark maze of guide rails, a process that seems to take a long time, that winds me through a place that seems too large. After a while, Ma cuts in to guide me again.

“Slow down, now,” she warns, “You’re just about there and we wouldn’t want you to run smack into that door! The release lever is in the center, a fire-door if you know the type. Just a press on that and you’re home free!”

I try, for several seconds, to find the door but my outstretched fingers reach nothing so I take a few careful steps forward. After another second, I feel a sniffling on my fingertips.

“Henry!” Ma exclaims, “You little trickster!”

I am trapped, here.

-traveler

What does it mean that I’m always behind the stranger?

‘The ‘Franklin County Rex’ is one of many tyrannosaurus statues that haunt the United States’ vast and tangled highway system. Its feet and underbelly make up a microcosm of graffiti, layers of evolving and conflicted styles, but its upper body has always borne the same message, ‘Sick? Send for Tyrannis!’ the slogan for an out-of-business medical consultancy and a phonetic butchering of the state’s motto.

Longtime residents of Franklin County insist that the ‘Franklin County Rex’ is on the move, that it is nearer, now, to St. Albans than it has been at any time in the past. That St. Albans is more likely expanding toward the statue is not an acceptable explanation for those that favor the myth. They are happy to show you sepia pictures of the ‘Rex’ in near isolation and pictures now of the ‘Rex’ at twilight, when some of the city’s notable (and historical) buildings can be viewed as silhouettes on the horizon. The King of Vermont has expressed, on several occasions, a dislike of the statue, calling it an eyesore.’

The ‘Franklin County Rex’ is burning, to the extent that anything made of cement can burn. Its paint cracks in the heat and there is a fleeting illusion of scales. A small crowd, a very small crowd, has gathered upwind of the smoke to watch the Fire Department’s attempt to stay the flames. It isn’t going well; the statue burns with unnatural ferocity.

“Must be something in the paint.”

“Arson, no doubt.”

“Stupid high school kid’s idea of a prank.”

What do they put up when a statue dies?

No, wait.

What does it mean to always be a step behind the stranger and why is his shadow so thick and why does it stand at odds with other, more conventional shadows? I have started to wonder if it isn’t all related somehow, if, being metaphorically behind the stranger means being literally in his shadow, and if his shadow is literally so thick, if it isn’t also figuratively a hindrance. I wonder how far a man his size can cast a shadow, and if he casts it like a spell or like a flat stone across a still lake.

There is a crack and the ‘Franklin County Rex’ shifts forward.

The gathered crowd gasps and murmurs. The Rex has moved; it approaches St. Albans after all. I forget the stranger, for a moment, and his shadow lifts.

The statue falls forward, the brittle cement of the ankles giving out under the weight of its body. It breaks into several pieces, each extremity tugging out its own portion of an ancient rebar skeleton from the torso. The fire finally begins to die down (“Probably the dust.”) and the crowd disperses. The stranger’s shadow re-forms like a storm cloud over my head in a sky that is already very dark.

-traveler

‘If you take the time to stop and wipe the scum away from the sign that welcomes you to Willow, you will see it boasts a population of 10,000: a tremendous number, considering the circumstances. The circumstances are rain- yearly, unending drizzle, a precipitation that has continued uninterrupted since the town’s inception, nearly 200 years ago.

The local language is gallows humor, the temperament, gray. It is humid in the summers and dreadfully cold in the winters: a soft, wet cold that almost freezes in January. Almost freezes, but doesn’t. Do not expect the lush grace of the tree if you plan to visit Willow. Expect the mild unpleasantness of a sip of water from a glass that has been sitting out too long.’

It is not raining when I arrive in Willow and the people are in some sort of giddy panic. Schools have let out for the occasion, restaurants and shops are closed. Those that remain open seem roundly abandoned, their employees standing outside to look up, up at a sky that remains dark and cloudy, but does not rain.

My motorcycle is loud, normally, but it is louder in the streets of Willow. People notice me and the awkward way I have to hold on to the broken configuration of my handlebars and because there is so little traffic on the road, their eyes follow me a long, long way. I find an inconspicuous park and pull in there, cutting the engine in time to hear a distant drumming of thunder.

Light is not friendly to Willow, it highlights a century of grime in the crooks and corners of things. Earthworms wriggle uncomfortably in the grass underneath a sagging wooden play place. Moss hangs off every surface, a crawling ecosystem in its own right. The air is thick and wet and still, the ground: spongy.

I walk for a while and have nearly reached Willow’s main street before I decide that the shocked stupor of the people around me leans toward a tentative happiness and not the foreboding I had mistakenly attributed it to. A kid rattles down the sidewalk past me on a brightly colored bike, two men smile quietly on a bench, and a group of teens gather around a card game outside a café, jeering at each other and laughing. The people of Willow could not be strangers to dryness, their town is not so big that they couldn’t drive a short ways for an hour’s reprieve, but it’s something else entirely to see your own home in a new light, and the locals here are experiencing that today.

The owner of ‘Wade’s Wetware,’ Wade himself, has declared a spontaneous sale for the afternoon- 20% off everything in the store, but I seem to be the only interested shopper.

“You must think we’re crazy,” he says, ringing me up for a motorcycle poncho, “We haven’t had a dry day here in generations, maybe.”

“I don’t think-”

There is yelling outside or, if not yelling, some sort of reaction en masse. Wade and I are at the windows of his shop in time to see a hole stretching open in the clouds, clear and blue. A thick column of sun appears through the gap, almost tangible in the thick mists of Willow. Beside me, Wade is mesmerized; his face and fingers dirty the glass.

“Never thought I’d see something like that,” he says, “Sunlight on city hall.”

People are falling in love with Willow, their dirty little town, staring at the chapel’s stained glass and the color of drab flowers back in the park. I wipe off the seat of the bike, wet from the air, not the rain, and make my way out again.

Rain begins to fall just as I near Willow’s border, and I wonder what repercussions a couple hours of sun will have. None, I would hope, but we don’t normally shine a light on a thing for the better.

-traveler

“Well, we had been walking most of the day at that point- totally off-trail through thick jungle. Like nothing you would see stateside. It was hot, our packs were heavy, and we were more than a little lost. But we keep seeing her- this old grandma elephant, anytime we come to a place open enough to let her through. Our guide, he didn’t speak much English, but he explained the elephants had trails all throughout the jungle. He said it was dangerous, that he didn’t normally take foreigners along them, but that we seemed like we knew how to handle ourselves.…”

“What was he worried about? Leopards or something? Snakes?”

“Poachers. They’ve got a law down here, anybody can kill poachers on sight. Poachers act in kind.”

“Jesus.”

“So, we started down this trail the elephants took and that same old elephant appeared ahead of us. ‘She watching us,’ our guide said, ‘See if we the bad men.’ He said we should follow her, but keep some distance. She saw us there and started to speed up but every time we thought she might be trying to lose us, she would be around the bend, waiting to see if we were still there.”

“That’s amazing.”

“It gets better. The sun was starting to set and our guide didn’t want us to be out much longer. We convinced him to go a little further, even though we hadn’t seen the elephant in nearly an hour. I was sore, man. My arms were sore from kayaking in- I found out later I was walking with a concussion from before- but how often do you get a chance like that? Finally, we came to a clearing and she was there! She had a whole family with her, she was the oldest, but there were a couple little ones there too.”

“Aww.”

“Well, I say little, but they definitely came up to my chest. ‘She invite us,’ the guide said, and we stepped into the clearing. ‘Old lady knows the bad men,’ he told us, and he showed us where the old elephant had been shot and survived.”

“That’s terrible.”

“Well, they had found their place in the jungle. We stayed for about an hour and just watched the little ones warm up and chase each other around. The ‘old lady’ even took some of our bananas and shared them with the rest. I don’t know a lot about religion, but out there in the jungle with those giants, that was the closest I’ve ever felt to God.”

‘It is a mistake to assume that hardship makes one event worthier than another and, yet, it is difficult to speak of successes without detailing a painful journey that preceded them. Perhaps it is endemic to all hostels, but ‘Wander Haven,’ with its oozing pipes and creaking floors, reliably brings these stories to the forefront of the weary traveler’s mind. It is a place that would attract no customers in a sane world but, because a night there has been dubbed a ‘rite of passage,’ it seems to thrive.

The author’s experiences lead him to believe that a hard-earned success and a lucky one are equal on all scales except by judgement of strangers. There is an amount of masochism that is expected among travelers and establishments like ‘Wander Haven,’ which exist to satisfy some need for self-affliction, fuel it. It is this publication’s view that pissing contests should be avoided when possible, particularly when victory amounts to passing the greatest number of stones.’

The ‘Wander Haven’ is truly unapologetic, selling a variety of ‘I survived…’ type merchandise at the desk and charging about as much as a low-tier motel. In its poorly ventilated common room, I huddle, in a corner, over my copy of Shitholes and unabashedly eavesdrop on the large gathering two tables over. It is the convergence of several traveling groups, of everybody who has walked into this room but me. They are young, younger than me, and pretty, prettier than me. They are dirty in the way travelers are often dirty, but they are energetic and they are optimists. Their light shines brightly against the dismal shadows of the ‘Wander Haven.’

I am drunk.

“I’ve hated every jungle I’ve been to,” a woman says, replying to the young man, “They’re stifling. Can’t see shit.”

The young man shrugs. He seems to enjoy hearing her swear.

“I’ve been back in the states all of a month,” she continues, scratching at a tattoo on her ankle, “And it’s fucking stifling here, too. In the three months before that, the only time I had something over my head was when it got too cold to sleep outside a tent. Give me the stars back!” she finishes dramatically.

“How was the trekking?”

“Fuck,” she says, “Hard. It started out hard and I told myself it would get easier but it just got harder. Each time you finish a climb you hear about something just a little higher with a view that’s just a little better. I met some guys along the way and we decided to do a climb one of them had done before. ‘Who needs a guide?’ they said, ‘There’s only one way to go.’”

“You got lost.”

“An understatement. We turned off a trail and got on the wrong ridge, ended up fucking tip-toeing across with a wall on one side and a sheer cliff on the other. Rain came in, as you might expect. Soaked the tents before we could get them covered. Rain became hail, hail became snow and it got cold. I was colder that night than I’d ever been. Everything was wet, nothing would burn. I put on every dry piece of clothing I had and hoped the water wouldn’t come up over the mattress and into my sleeping bag.”

“But you survived.”

“That’s not the end of it. I finally fell asleep, fucking shivering, and I wake up in the middle of the night to this creaking. No wind, no trees nearby. My brain’s trying to piece the thing together and just as I realize it’s one of my poles bending under the fucking snow, the whole thing collapses on top of me. I end up crawling into the guys’ two-person tent, you bet they fucking loved that.”

“And you still miss it?”

“Well, the next morning the sun came up and I got out of that fucking stuffy tent as fast as I could. I stepped out into the snow and the sun and I was finally fucking warm. Up on that peak you could see for miles- not a cloud in the sky. The mountains around us were white from the storm, the sky was bright blue, and there probably wasn’t another person in three miles.”

“And you saw God in the mountains?” someone jokes, jabbing the elephant guy.

“God was in the fucking storm.”

A solemn sort of quiet passes as the group seems to let out a collective breath. One of the men, at the far end of the table, breaks the silence.

“You don’t really notice the character of places until you’ve gone through something like that, huh?” he asks, “You just take shitty situations personally and shut down to whatever might be redeeming about them. How many people would walk into the lobby of this place and just walk back out without ever giving it a chance?”

They all nod and I take a drink from my water bottle, thinking it’s time to start on the road to sober. The water goes down wrong and I choke and cough and make a scene in the relative quiet that had existed in the room before. When I’m able to breathe again I turn to see everyone looking my way.

“You want to join us, man?” the elephant guy asks after a moment.

“No…” I sputter, “I should head to bed.”

“You look like a guy with a few stories.”

“Not me,” I tell him, “I live a pretty… straightforward life.”

“I saw you come in on that bike parked out front,” the mountain woman insists, “What happened to your handlebars?”

“Stupid driving,” I tell her, “And a sharp turn.”

“You race?” she asks, and I sigh.

“On that thing? Look, I was checking out this stretch of road a few hundred miles east of here that’s supposed to be, uh, shorter than it is. I’d taken it a few times because, well, in order to disprove something you’ve got to show your work and I kept cutting milliseconds off my expected drive time.”

“You think this road is like a teleporter or something?”

“Not me,” I insist, “But some people think something kind of like that.”

I look around the table and see I’ve already lost a few of them but, because the blonde guy is still listening, I continue:

“So, some of the people reporting this said that if you take the curve just right, you hit this series of little bumps and divots that reverberate up through the wheels and sound like a song- they build highways like that in Japan I think. Anyway, that’s supposed to trigger it.”

Even the blonde guy is starting to look doubtful now.

“Long story short,” I say, “I thought I had finally gotten it right, like, there was this rhythm just on the edge of the road that sounded like a song coming up the spokes of the bike. I thought I had gotten it right…”

And then I was somewhere else entirely.

“And then… uh, a squirrel ran out. I stupidly, well, you know…”

“Nothing stupid about that,” blonde guy says, “You’re out there long enough and you realize that the lives of animals are as sacred as our own.”

“Yeah…” I say, running my hands through my hair, “Yeah…”

“Where’d you hear about that road?” mountain woman asks, but a door slams above us before I can answer.

There are frantic footfalls in the stairway before another woman bursts in and runs to blonde guy.

“There’s something in the wall up there,” she says, “Like a fucking mold dog!”

“It’s probably just a spider…” he croons, but she hold up a boot that looks like it could have spent a year on the side of the road.

“It ate my fucking boot, Donny, it’s not a fucking spider.”

“It came out of the wall?” I ask, “Through a hole about a foot across?”

“Have you seen it?”

“Something like it.”

“What am I supposed to do?”

“Leave it the boot,” I say, standing to go, “And tell the story when it’s been long enough to be funny.”

-traveler

© 2024 · Dylan Bach // Sun Logo - Jessica Hayworth