I arrive at ‘The Watery Grave’ well before low tide and wait, for some time, for the water to ebb and slough off the rocks below the surface. It has been a scattered few weeks, with my shadow and the stranger (a shadow, of sorts, himself) a potential in any dark corner or unchecked crevice. Neither manifest and I wonder if I am lighter for all that the stranger is weighed down- able to move through the world with greater ease.

I don’t doubt that they are following, though, so I park the bike in a storage facility, in a room my family has rented but forgotten. There are pictures of me there, as a child, as a young, healthy man. I spend longer than I should, and then I set a course for a destination I have avoided many times, for having often been in the area.

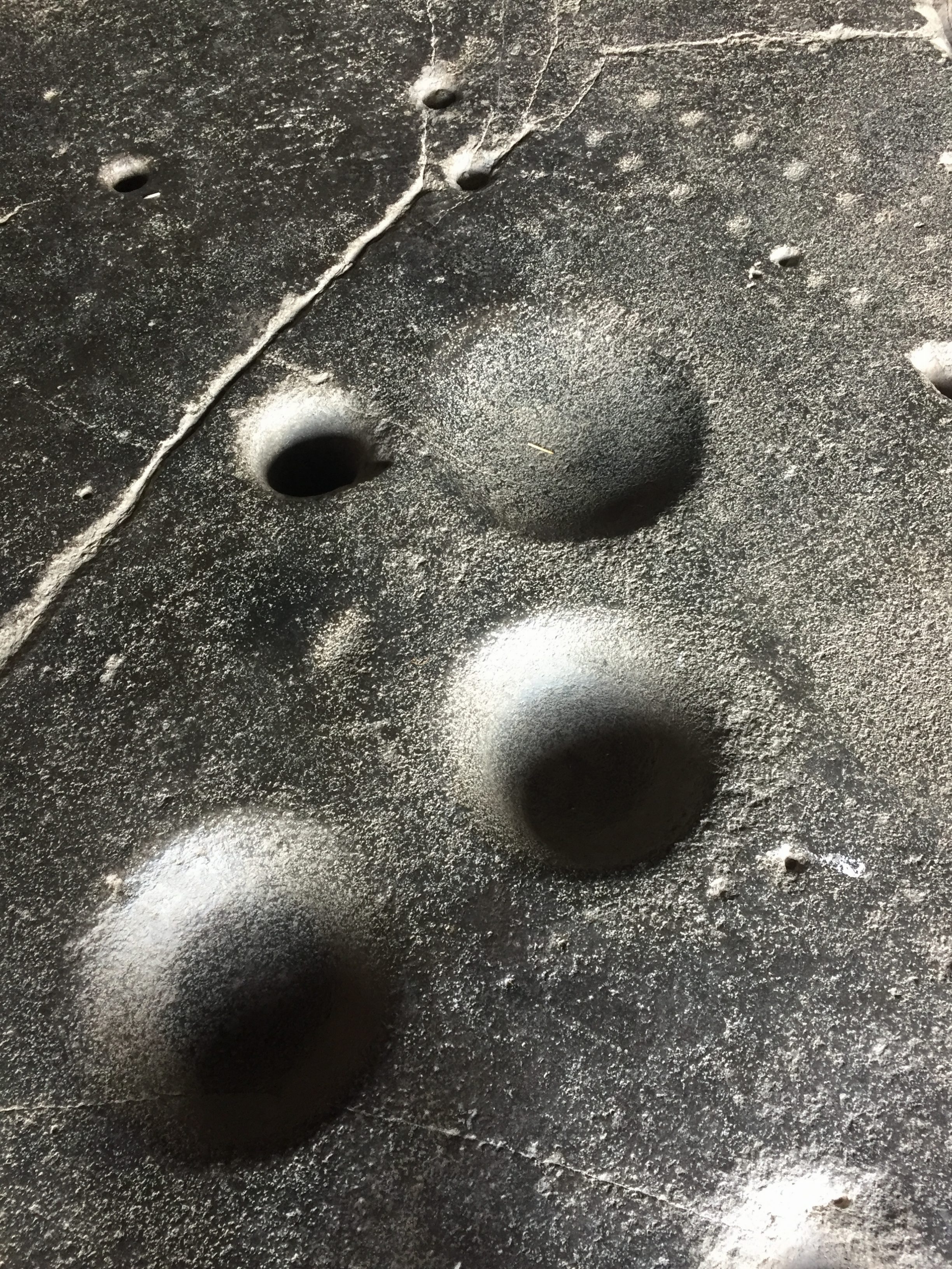

‘As the sea pulls away from Clementine Rock, one might stop to marvel at the life left scurrying in the tide pools, this round’s losers of the reincarnation cycle. Marvel carefully, reader, for among those pools is a dark, lifeless place: ‘The Watery Grave,’ one of the world’s many dead-ends.

‘The Watery Grave’ is among the most literally named entries in this humble tome, having taken dozens of lives over the course of the last decade despite guards, warnings, and razored deterrents. It has developed twin reputations- one being that it is a spiritual place and the other being that is a challenge to survive. Those combined aspects are a catnip for a certain type of mid-twenties white college-goer, the kind of person looking to add to their repertoire of hostel stories or personally meaningful tattoos.

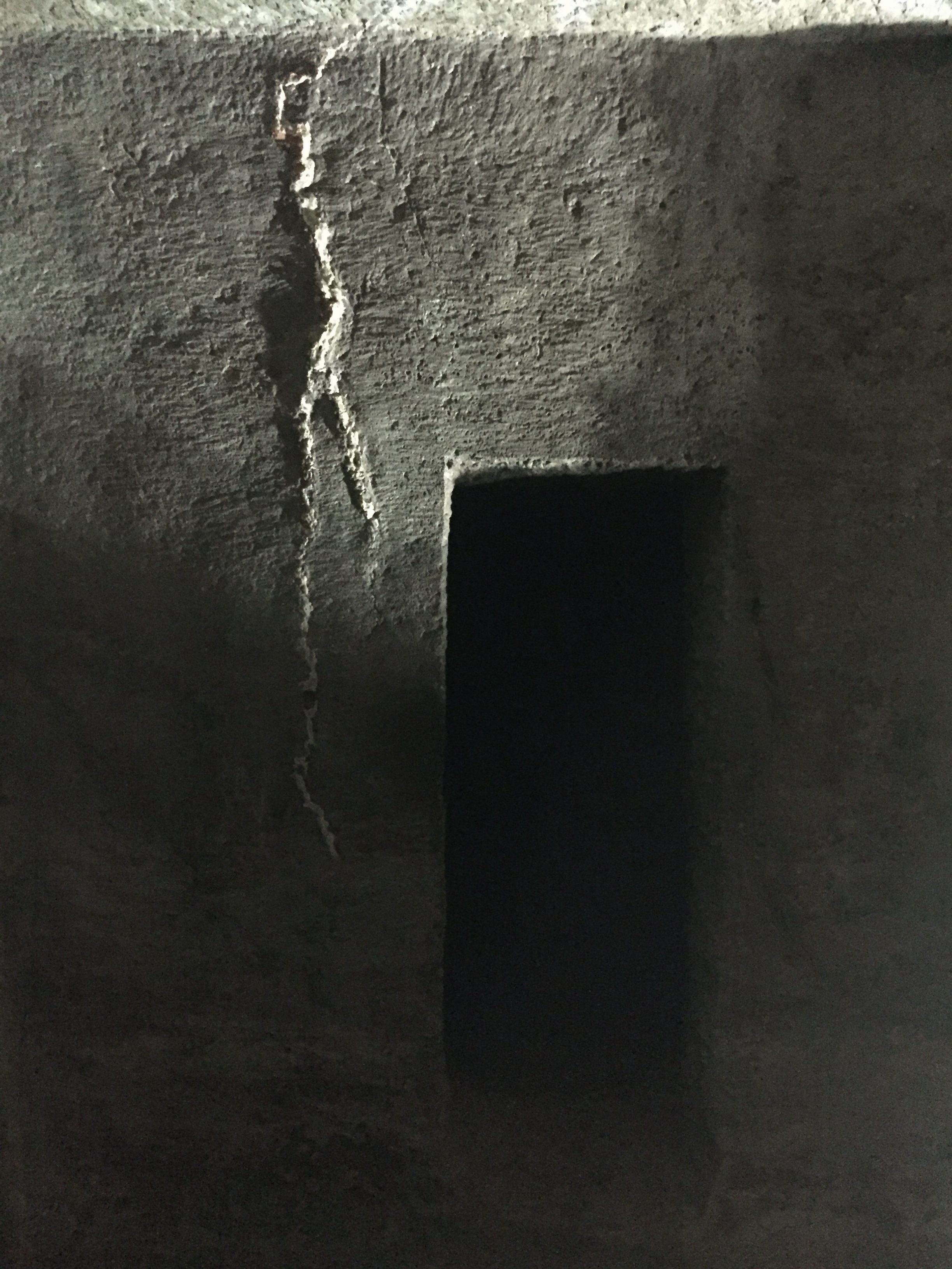

The spiritual stories describe the main cavern as a natural sanctuary, a wide, smooth room, cut off from the world by the ocean itself and totally still. Totally dark. Some, who have stayed a while in those depths, hear the ‘The Watery Song,’ an aural hallucination or a blessing, depending on who you ask. The challenge, assuming one has packed for their stay, is surviving the entry and exit, a trial that involves wading into the failing tide and riding the sinking water as it lowers you to its terminus, where a winding tunnel, sometimes just 3’ wide, leads to the sanctuary. This is the difficulty, a race against the water as it begins to rise again, faster than many think, cold, dark, and unrelenting.’

I step out to Clementine early as well, hefting my water-proofed bag over my head and slipping into the sea’s potholes, ending life there with sharp crunches. ‘The Watery Grave’ is easy enough to find- the ranger’s latest deterrent, an iron cage, has rusted and pulled away, standing like an apocalyptic tree in the waves.

I begin the descent, slowly, treading water and sputtering. The way down is narrow and sharp, lined with clams that click and clatter, that cut my arms and my feet until I am churning a pink froth. I consider going back, finding some other way to throw the stranger, but by the time I lose my nerve I see that I have sunk too low, that the only means of escape would be rescue.

The descent further narrows, a place where the clams have clambered over each other to squeeze off access. My bag will not fit as it is. I try to strip things out but the water drains quickly, it drains so that I am hanging by the bag itself for a moment. Something gives way and I fall, shredding the skin from my shoulders.

In time, I feel the bottom.

I start in the tunnel as soon as there is an inch of water to breathe, away from the sunlight, to a place where shadows cannot be cast.

-traveler

‘‘The Once-Quiet Clearing’ outside of Langston remained a secret in its prime, its location and existence guarded by the locals through a silent understanding: that it was too good for the world’s eye. It was maintained entirely by the care of its visitors, by the picnicking families and the amateur yogis and the various plant, bird, and cloud watchers. ‘The Once-Quiet Clearing’ provided a wholesome nothing- an empty space and the soft, general silence of a sleepy forest. More than that, ‘The Once-Quiet Clearing’ seemed to sand the edges off sound. Through some acoustical quirk, it was simply difficult to make noise there.

And then, there was a murder.

A man was stabbed to death with no fewer than 15 people in the nearby area, all of whom reportedly heard neither struggle nor scream. An investigation began, a suspect was apprehended, and the case was closed but not before the strange circumstances of the initial killing broke the monotony of a slow news day, first regionally and, eventually, nationally.

With that, the world’s eye turned and saw, for the first time ‘The Once-Quiet Clearing.’

The clearing’s silence became a novelty- a challenge. People arrived with every instrument of sound known to man and battled the noise-dampening effects as part of mystery-themed tour packages. A smaller sub-group of visitors came alone, looking for a place to make their confessions or tell their secrets. They knelt to the ground and whispered to the grass like members of a loose cult. After a year of these brutal attentions, ‘The Once-Quiet Clearing’ began to gray.

The clearing remains open and the way is well signed. It is still, for the most part, a quiet place. These days, the clearing is better known for a distinctive rattle- the rustle of dried leaves and browned grass. It is an autumnal sound, initially soothing, but increasingly like the deep cough of the profoundly ill. It is a place, now, that sours thoughts.

-excerpt, Autumn by the Wayside

“A man’s shadow is his worst self,” the stranger says, placing himself in front of the exit, “And yours has been sticking to my feet like dog shit since ‘The Edge of Disaster.’”

I look around for a weapon, for anything that isn’t made of wax. A fire extinguisher falls to pieces in my hands and the stranger frowns when I throw the largest at him. The chunk of wax crashes into the wall over his left shoulder and shatters further.

“I don’t know how you live with this,” he says, gesturing to my shadow, “I didn’t know a man could cause himself so much suffering.”

The room’s lighting dims and twists into prisms as his shadow extends into a pool at my feet.

“You were trailing things when this happened,” he continues, “And, would you know it, those things are trailing me now. This spot o’ haze has been dragging like an anchor all these long months, shortening my days like a head cold. And the money I’ve spent trying to banish the thing… Turns out, a spare shadow might as well be a sign hanging about my neck: ‘This man’s got an expensive problem.’”

My own feet move lethargically. The stranger’s shadow holds them to the floor.

“I hit up every mystic between here and Boston before I started to wonder if maybe this weren’t the only hanger-on. So I come here, and I see this building, and I see this display, and I see the one in the next room too. Walk with me, old friend.”

The stranger moves from the door and I leap for it, falling flat in the stretch between. He pays no attention, and as he walks I feel myself dragged, and as I drag, the light changes to accommodate the opposing shadows.

I slide through a doorway and down a set of three cement stairs, rolling to a stop at my own wax feet. In this room, I am shown in the lobby of ‘The World in Wax.’ I am politely declining membership.

“And, how about the next?” the stranger asks.

His shadow drags me through another doorway, into a dark room with a raised display. Propped on my elbows, I am level with the eviscerated stranger. He lies on the floor of a dirty public restroom, empty except for a pair of legs visible from under the door of a stall. The legs are all bone and tight, white skin, bound together by dusty blue jeans and old, leather shoes.

A sliver of dread pierces me.

“What is it?” I ask, “Did they model it? Do you know what it is?”

“You didn’t know?” he asks, shoving the door open, “It’s your goddamn worst self.”

The thing in the stall is undoubtedly me- a me with matted hair and a stomach that bulges obscenely. My wax mouth gapes for missing teeth and thick lumps, like bug bites, darken my arms.

“That’s what’s following me now,” he says, “That’s what was following you before. You’ve got a shadow so mean it gambled against you when I pushed you off into that storm. It left you for dead. Now, I need you to take it back.”

“Do you have one of those?”

“I’m the worst me there is, now, take it back.”

“Is…”

“Look,” the stranger says, his voice growing quiet and serious, “I’ve not been still more than three days before that thing shows up and I’ve been waiting here for you just about as long. You best-”

In his hush, we both hear the creak of the front door, two rooms behind us. I scramble to my feet and topple again as the stranger steps backward into a corner. His shadow tightens and holds me in place, an inky vice. Footfalls approach, slow and quiet. A floorboard groans in the next room.

“Someone there?”

A man in security uniform peers around the door frame, clearly unaccustomed to threats at ‘The World in Wax.’ He sees me on the floor and, as he swings his flashlight around to the stranger, its beam cuts through the shadow holding me.

The stranger shouts but I am well on my way before either of the men can react. There is a collision of bodies behind me, and a struggle, but nobody stops me in my hasty retreat from ‘The World in Wax.’

-traveler

‘‘The World in Wax’ holds dearly to its ‘number four’ ranking in ‘Travelz Magazine’s Top Places of Nominal Interest to Those with Eccentric Tastes,’ an award given once just before the magazine (and the industry surrounding it) folded like the cheap paper it was printed on. It is a sprawling complex, surrounded by the suburbs that seep out of Greenville and lit up massively at night.

The psychic, Alyssa Crystal, and her unspeaking husband have voiced and gestured ‘deep, spiritual concerns’ regarding ‘The World in Wax.’ In a 2013 interview, Ms. Crystal would say only ‘It is too knowing, as a place,’ and Mr. Crystal would later agree, coughing loudly into the microphone and waggling his eyebrows.

Stripped of context, ‘The World of Wax’ is simply a large, themeless wax museum that prides itself on accurate depictions of normal people doing normal things. Most visitors will enter and leave without a second thought but others, those who recognize loved ones among the varied wax statues, may reel at the accuracy at which they are portrayed and wonder at the so-called ‘normalcy’ of their fellow man.’

Alice chooses ‘The World in Wax’ when I am left, aimless, at the steps of ‘The Park Ranger Retreat Grounds,’ one of the spilled toothpicks having slid between the pages and pierced an unmarked entry. It’s a long drive, likely with many potential stops in-between, but I am superstitious as it suits me and I believe in Alice, the ghost of a woman I never met, like some believe in God.

I arrive early on a Thursday morning and wait behind a group of elderly women who glance nervously between themselves and say nothing except the few words necessary to purchase their entry tickets. The man behind the counter tries to sell me a membership and I decline, though I am surprised to learn no single exhibition is up for more than a month.

“What do they do with all the old figures?” I ask.

“Melt them down,” he shrugs, “Reuse the wax,” and, while I don’t think that is feasible or true, I nod and move on.

Past the small lobby, I enter onto the grounds with its myriad buildings and walk among the stiff, waxen grass that rattles warily in the shifting air. Alice, between my teeth, offers no particular lead so I pick my own way through the complex, admiring, for a while, the scene of a grisly crime, a frozen day at the beach, and a tired looking wax figure looking over a newspaper on the toilet.

The size of the complex is staggering and, without clearly marked paths or printed guides, I am left to determine what is and isn’t an exhibit on my own though, as time passes, it becomes clear that everything at ‘The World in Wax’ is made for viewing. Wax leaves gather in gutters and wax roaches huddle between dusty cans in a wax grocery. I peer through the just-parted shades of a window and spy a wax couple in bed, with seemingly no other viewpoint available. One of the men’s eyes are opened, as though startled by me, a noise outside their window.

Eventually I catch up to the older women, they having huddled around another bedroom scene, this one in plain view. They are locked in a soft-spoken argument, their voices like slippered footfalls, and I eavesdrop from a polite distance. I gather that they recognize the figures there and I walk over, as though innocently making my way through.

“Don’t let him look!” one of the women snaps to another but they, as a whole, seem at a loss as to what to do. I am a dirty-looking man, a stranger to them, and they don’t know I am a coward, that I would be turned away with a single stern word.

“Doesn’t matter,” another says, “Harold’s the one putting himself on display.”

I pretend not to hear any of this in a way that I’m not sure is totally convincing and they press to the wall in order to allow me my look. An elderly man sits up in his bed, nude except for a modest portion of sheet pulled over his legs. Lying near him is a woman- she reaches out to stroke his back.

A sign above the scene reads: ‘Infidelity.’

I give the women their privacy again and wander back toward the exit, stopping, on a whim, at a building labeled ‘Roadside Attractions.’ There, in the first room, an incredible reproduction of the stranger, of the first stranger, stares into a frozen campfire. The backend of his pick-up truck protrudes from the wall and his thick shadow spreads itself across the ground behind him. Ignoring the security cameras (which are suspiciously waxen themselves), I step into the edge of display to see what strange haul the man carries in his truck these days. There, in wax chunks, is a second stranger, its split head bearing the same pensive frown as the living man that now stands from where he sat.

“I have something,” he says, “That I think belongs to you.”

His shadow frays and mine emerges, as though from underneath, pinned under the stranger’s heavy, black soles.

-traveler

I am accustomed to surprises, this far into my travels, but I have not grown to like them. I am greeted by many of the rangers like a lost child- like a child that has been lost for an hour or so- like a child that was lost for such a short amount of time, nobody noticed until he returned. Their friendliness is a little too sweet. They use small words and short, sticky sentences when they speak to me. Most of the conversations I have are short, and most consist mainly of greetings and goodbyes as the man from the front, Ranger Chuck, leads me to a warm office in the back.

“Got a picture of you from the last time,” he says, settling in behind his desk and gesturing for me to take a chair opposite.

He spins a framed photograph around so I can see it- Ranger Chuck with someone who could certainly be me.

“It’s blurry,” I tell him.

“Well,” he says, a frown turning his face for just a moment, “Ranger Paul got his finger in the corner there and it threw the focus off.”

He leans back and stretches, straining the plastic office chair, and says nothing.

“So… can you explain this to me?” I ask after several, quiet seconds, “Is this time travel or amnesia or something?”

“Not totally sure,” he says, brushing invisible dust from his desktop, “You just show up here out of the blue every so often without any rhyme or reason, telling us the box up in Birch sent you. Thought it was a joke at first but…”

He pauses.

“Well, what would be the point? And you’re earnest, kid. Damned earnest.”

“Earnest?”

“Not in the typical way. You’re a real sourpuss much of the time, but you seem like the type that believes what he says.”

“What do I say?”

“You tell us what you’ve seen out on the road, mostly. Remind everyone to read your blog.”

“And you do?”

“Well… let’s say I’m a little behind.”

“So you know nothing about this?”

“Not nothing,” he says, “You ready for the ranger spiel?”

“Sure.”

“The Wayside Park Rangers is an international organization established to preserve the world’s eccentricities. In practice, it’s several loosely connected sects of conservationists with niche interests. We operate behind the curtains for the most part, not because we’ve got any ‘cloak-and-daggers’ agenda, but because drawing attention to the places we protect tends to be contrary to their conservation. We operate on donations and pay next to nothing, if you’re thinking about asking for a job.”

“And where do I fit in?”

“Well, that’s the question, isn’t it? The latest theory is, well, you know something about the ‘path,’ don’t you?”

“Something.”

“About as much as we do, I imagine, which is to say that it probably exists. We stumbled upon it as we started to digitize our records into a single, central database- the same names popping up in registers over and over again, like people were following some sort of guide.”

I start to pull Shitholes from my bag and he smiles.

“We know about your book and it’s not that. Or, it might be that now, but our records suggest this has been going on since before it saw the printer. Folks- certain folks- are drawn to these places.”

“And that’s the path.”

“That’s what seems like a ‘path.’”

“Is there a… direction?”

“That was our next question. Looks like: yes. We’re still working on just which way it leads, however. Lost a lot of files to rats, fires- you name it. It’s like putting together a jigsaw puzzle but you’ve got to wander around finding the pieces as you do.”

“So, I’m one of these people?”

“You are,” he says and, sensing what I hoped was a very private disappointment, he adds, “But there’s something more to your case. Yours and a few others. The way we figure it, there are four types of people involved in this mess about the path. There are the rangers, of course, who look after it, the ‘tourists,’ who walk it and don’t realize, the travelers, people like yourself that move with a bit more intent and…”

“The strangers.”

“The strangers,” he agrees,” Who seem to want to tear the whole thing apart. You were the first to turn us on to them, actually, and, sure enough, the moment you start looking at disasters along the path, you get these descriptions of short-haired men and jerry cans.”

“What are you doing about it?”

“Well,” he sighs, “Nothing.”

“Nothing?”

“Nothing,” he confirms.

“But-”

“I know, because I’ve heard it from your own mouth, why they don’t fight forest fires in Yellowstone. Care to remind me?”

I frown and say nothing.

“Turns out, we’re not always as smart as we think we are. Sometimes a problem is just another part of a well-oiled machine, complex beyond our current understanding. The path is complex, [traveler], and we understand almost nothing about it.”

“So you let them… burn things?”

“And we let you wander in and out of here on a whim, my friend. We let you tout your book and your blog and we let you think you know more than us even though you show up here knowing less than when you left.”

“You think I am part of the path?”

“Son, your name come up so often in our registers that you might as well be paving the thing yourself.”

-traveler

Rear View Mirror

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016